The Museum Puri Lukisan in Ubud has invited me to curate an October 2013 exhibition of Balinese wayang painting from 1900 to the present.

I’m returning to Bali on April 4 to work out the details and visit the collections of other Balinese museums from which we hope to borrow pieces of wayang art to supplement the 60 paintings we already have from Ketut Madra’s and my collections.

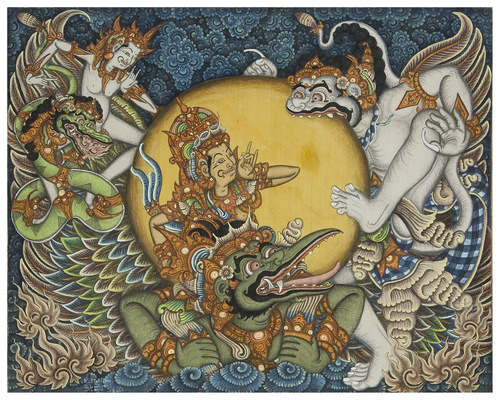

Below: Hanoman and Sangyang Surya by Ketut Madra. Acrylic paint on canvas, 54.5 x 44 cm., 1972

The first exhibition of this work took place 40 years ago at Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum in the summer of 1974. Here’s the Boston Globe review of that show:

The Boston Globe, July 28, 1974

Exhibition breathes the life force

by ROBERT TAYLOR

“The Legendary Paintings of Bali” – actually 19 paintings, three drawings, five masks, three knives, two small ivory carvings, two sculptures and two shadow puppets of translucent buffalo parchment – at Cambridge’ s Fogg Art Museum through August comprise what is in all probability the first U.S. exhibition of Balinese art.

The Netherlands, thanks to old colonial ties, has experienced the art and culture of Bali and from time to time occasional pieces dot the Western scene; but, small as it may appear, the Fogg show, mostly on loan from David M. Irons is a rarity. It has been arranged in three rooms following the layout of a Balinese temple. The traditions and ties of the island of Bali are, of course, Hindu. While Islam has triumphed in the rest of Indonesia, Bali remains the only part of the archipelago still subscribing to Hindu beliefs, which traveled to Java and mingled with the island legends and animistic worldview about the year 1200. Thus, the ‘temple’ format of the exhibition roughly observes a progress from the least sacred, or southern section of the temple, to the holier precincts, which face northeast.

What you will find in the southernmost room are depictions of gods and heroes in their violent manifestations. They are figures with several heads or arms, a distinct advantage in any sort of combat, but at the same time these peevish gods and valiant warriors are comic. Magical though they may be, art itself presents a point-of-view toward them. The gods of ancient Greece in their all-too-human failings suggest the qualities of their Balinese counterparts. Brahma and Vishnu are quarreling, for example, and like rabid pagodas, have assumed protective stances – actually the fearsome ‘pamurtian’ guise in which they multiply in pyramidal forms – but Shiva, between them, robed in a golden aura, spreads to the edge of the universe, shaming the others and making them aware of their bluster.

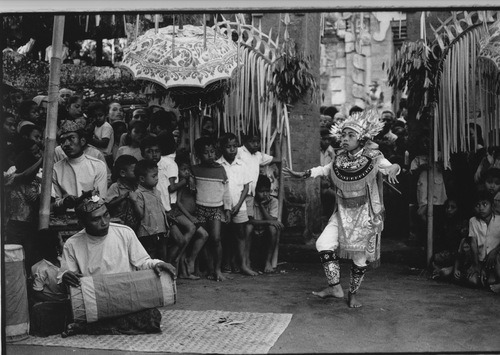

If the demonic and the marvelous fill this room, the middle room is largely devoted to the turbulent Hindu epics of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Hanuman, the divine monkey, slays the naga, or serpent. Sita is abducted by Ravana. In a charming touch, a large painting, flanked by the actual puppets, depicts a Balinese “dalang,” or puppet- master, enthralling an audience with a shadow play of the Ramayana.

Finally one finds the Balinese cosmology given quieter and more meditative aspects. The third room is by and large metaphysical. A schematic map of the gods places Sanghyang Widi, the unmoved mover, at the center of the universe, the one god who sets the eternal dance in motion. (I trust that the cosmic scheme of things will survive the frisky description of the chakra of Vishnu as “the disc at the top which resembles a spiked Frisbee with razors’ edge.”). But this room also contains the dance masks with their conventions such as the graceful arch for the eyes of the aristocrats and potato noses for the clowns.

The paintings range from the last 120 years to the moment, and among the features of the show is the element of contrast between the old-time wayang painters of legend and moderns like Ketut Madra who follow the traditional imagery, but who employ contemporary materials.

The ancient methods use ground pigments mixed with limewater and a fish-based glue. Cotton cloth, on which the picture is done, first gets prepared with a rice paste, then dried in the sun. Polished with shells, the cloth is draped in the lap of the artist, who works with six basic colors: red from imported Chinese vermillion, yellow from clay, blue from indigo, ochre from native rock, black from lamp soot, white from calcinated pig bone.

Line controls form in Balinese art. The quality of the line derives much of its subtle character from a pointed bamboo stylus; in any case, drawing is fundamental. This show raises original stylistic issues, which have been little explored, in particular the relationships between Balinese art and the styles of Tibetan Mahayana work; and the masks which bear an affinity to the Japanese Noh drama. Some pieces such as the “langsé,” or temple hangings, suggest ideas in contemporary Western art (the desire to close the gap between craft and high art, the use of textured floral contrast, the incorporation of objects, such as pierced coins, which suspend one of the hangings.

There is a single cloth scroll, faded by the southeast trades and the southwest monsoon winds: no one tries to preserve Balinese art. From our Western point of view it is unfortunate; but the Balinese do not substitute art for religion as Western man has sometimes sought to do, and their art is not mummified but intended for the experience of being alive.